Reflections on Glastonbury: A Personal Journey

I’d like to talk about my visits to Glastonbury and the photographs I took while there. Over the past several years, I returned multiple times to visit my family—and especially my father, who was unwell. My son was also traveling back and forth, and so Glastonbury remained a central place for all of us, even after we moved to Finland. My family lived there for over 20 years, and returning always carried a deep sense of nostalgia.

However, going back felt strange. I didn’t feel like the same person who had left. Walking or cycling around the town brought back many memories. I bought an old bike in Bath—a fixed-gear that needed some work—and fixed it up to use around Glastonbury. Even as I revisited familiar streets, I felt different, like a version of myself that didn’t quite belong anymore.

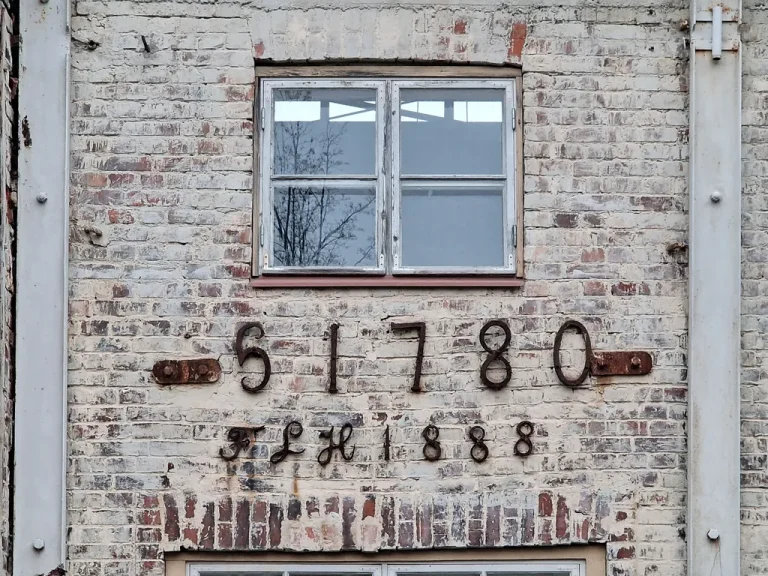

After my father passed away, my ties to the town became more tenuous—now mostly through family friends who still live there. The photographs I took reflect this tension. They capture contrasts: the lush countryside outside the town center, and the forgotten brownfield sites on its edges. These spaces, both decaying and alive, stand with one foot in the past and one in the present.

Many people who live in these marginal places around Glastonbury lead alternative lifestyles. They often reject mainstream culture, choosing instead to live in caravans or makeshift homes—some of which were present during my visits but have since disappeared. Their absence speaks to a broader issue: I believe there’s a serious problem in how England treats people on the margins of society. These individuals deserve more respect, support, and dignity. Glastonbury, after all, has always been a place that welcomes difference—a place where you don’t have to fit in to belong.

That’s part of what makes Glastonbury so special. It takes all kinds of people to make a community, and Glastonbury has long embraced diversity—whether it’s New Age spiritual seekers from around the world or locals with unconventional beliefs. In many ways, not fitting into a norm is the norm there.

The photos I took of the derelict areas aren’t meant to criticize, but to highlight Glastonbury’s layered identity—a visual kaleidoscope of history, culture, and transformation. Glastonbury is also known by another name: Avalon, tied to the legends of King Arthur and Queen Guinevere, who are said to be buried at Glastonbury Abbey. This mythic connection adds to the town’s mystique and significance in British culture.

Today, Glastonbury is perhaps most famous for the Glastonbury Festival, held on Michael Eavis’s farm about 10 kilometers from the town itself. Though technically located in the village of Pilton, the festival has adopted the name “Glastonbury” because of the town’s strong associations with alternative and spiritual culture. It’s one of the biggest music festivals in the world, and when people search “Glastonbury” online, they’re far more likely to find information about the festival than the town. This can be frustrating for residents, as the festival and the town are quite distinct.

Beyond the festival, Glastonbury hosts a wide range of events—spiritual conferences, gatherings of different faiths, UFO conventions, and the annual Goddess Conference, to name a few. It draws people from all over the world, and despite no longer living there, I remain nostalgic for it. It was a formative place in my life, both personally and creatively. Seeing photographs of Glastonbury now evokes memories not just of the town, but of England more broadly.

When I lived in England, I couldn’t always see its beauty. It was only after moving away that I came to truly appreciate it. The graffiti, caravans, dereliction, and elegant shop windows in my photographs capture this complex beauty—one rooted in deep history and cultural richness.

I think many people experience this sense of dislocation—of exile, even. Living in a country that isn’t your own often brings a new awareness of what you’ve left behind. Yet despite this longing, I don’t feel a deep connection to any one place. I was born in Wales, and while I do feel what the Welsh call “hiraeth”—a deep longing for home—it doesn’t mean I would fully fit into Welsh cultural life either.

In Glastonbury, I often felt like an outsider too. I’ve never quite felt that I truly belonged anywhere. Perhaps my life has been a search for belonging—or a questioning of why I don’t feel I belong at all. In that sense, I feel a bit like a Christ-like figure, wandering without a fixed home or identity.

Some people grow up in places with a strong collective identity—like the industrial towns of South Wales, where heritage runs deep. But I’ve always stood slightly apart. Glastonbury, for all its uniqueness, was never quite “mine.” Still, it remains a significant part of my past and my identity—both as a person and as a photographer.